The Loop Chicago Part 3

- Dec 22, 2025

- 36 min read

Updated: Feb 8

In this series of essays, I explore the sights and scenes of Chicago’s Loop. Post 1 outlined the Loop’s borders and my walk along Michigan Avenue, while Post 2 chronicled State Street and Wabash Avenue. In this installment, I head south on Clark and retrace my steps north on Dearborn.

N-S Street 4: Clark Street

Chicago Loop Synagogue

My first stop on Clark was the Chicago Loop Synagogue at 16 South Clark:

Most Indians, myself included, have a sketchy sense of who the Jews are, so here is a brief introduction.

The story of the Jewish people unfolds along two strands: a scriptural narrative and a historical one. The principal source of the scriptural narrative is the Bible. The point at which the canonical chronicle begins to align with historical evidence is debated, but thankfully this essay does not seek to adjudicate the Palestinian dispute.

Jewish history shows a recurring pattern of migration into and displacement from their scriptural homeland. There are four seminal events of inward migration, the first two of which are exclusively biblical and the latter two historically attested.

The first movement is that of Judaism’s foundational figure, Abraham, whom religious tradition places around 2000 BC in Mesopotamia. The earliest biblical texts, composed centuries after his putative lifetime, draw on oral traditions and thus cannot be historically verified. According to Genesis, God forms a covenant with Abraham and commands him to travel to Canaan—believed to be in the region that includes modern-day Israel—the “Promised Land” his descendants are to possess forever. In accepting the covenant, Abraham affirms belief in a single God, departing from the polytheism of his time.

The family settles in Canaan, where God renames Abraham’s grandson Jacob “Israel,” a Hebrew term meaning “one who wrestles with God.” Jacob’s twelve sons become the patriarchs of the twelve tribes of Israel. At this early stage, “Israel” is not the name of a place but of Jacob himself; his descendants living in Canaan are Israelites. A famine forces Jacob’s family to migrate from Canaan to Egypt, where their descendants expand into a large community over several generations. As their numbers grow, the pharaohs begin to view the Israelites as a threat, leading to their enslavement.

The second return to the holy land is precipitated by a pharaoh’s order to kill all newborn Israelite boys. A mother hides her infant in a basket on the Nile, where he is found by the pharaoh’s daughter, given the name Moses, and raised in the royal household. Moses later leads the Exodus, guiding the Israelites out of Egypt and through the wilderness, but dies before they re-enter Canaan. His aide Joshua then leads them into the Promised Land.

The date traditionally assigned to Joshua’s entry—around the thirteenth century BC—also lacks historical verifiability. Jacob (aka Israel), Moses, and Joshua, like Abraham, are scriptural figures held to be real within their faith traditions but are not confirmed by independent historical evidence.

Over time Joshua's descendants in Canaan divide into two kingdoms: Israel in the north and Judah in the south. Now “Israel” becomes the name of a territory, not just a people. From this period onward, the biblical narrative becomes anchored in a historical record, though the events described in the Bible need not be taken literally. Archaeological discoveries attest to the existence of both Israel and Judah. For our purposes, we can now leave the realm of scripture and step into history.

The northern kingdom, Israel, is destroyed by the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BC, while the people of Judah are conquered by the Babylonians two centuries later. The residents of Judah are exiled to Babylon, in what is now Iraq.

The third inward migration occurs in the 6th century BC. Barely fifty years into exile, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquers Babylonia and permits the Judahites to return home. The land they return to—now a Persian province—appears as Yehud in Persian administrative records and as Jerusalem in the Bible. These returning Judahites gradually come to be called Yehudim, people of Yehud, a term that eventually becomes the English word “Jews.”

In the five centuries after their return from exile, the Judahites—now increasingly known as Jews—live under Persian rule, rebuild their community, fall under the Greek empire of Alexander the Great, briefly regain independence, and eventually come under Roman domination near the start of the first century. During this Roman period, a figure appears who will reshape world history: Jesus of Nazareth, born into a Jewish household far from the centers of power.

By the 7th century CE, as Roman rule ends, Christianity has become the dominant faith, and Jews are increasingly marginalized within their scriptural heartland. After the Romans lose control, the region falls under Islamic rule for more than a thousand years, during which sometimes they are embraced in their Promised Land and other times when they are not. After the First World War, the area becomes a British mandate for a brief span.

The fourth major movement of the Jews into the holy land occurs when the modern state of Israel is established in 1948.

From Abraham’s covenant with God to the creation of modern Israel—a span of nearly four millennia—the Jews have shown a persistent attachment to the land now so fiercely contested. Their migrations have been repeatedly punctuated by displacement. From the Assyrian and Babylonian conquests to periods of marginalization under Roman and Islamic rule, Jews moved outward again and again, often encountering entrenched discrimination across Europe long before the horrors of the Holocaust. This long arc of exile produced one of the world’s most remarkable diasporas—remarkable not for its size, for Jews were always a minority, but for its achievement. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the United States became one of the least anti-Semitic destinations for successive waves of Jewish immigrants—and continues to be enriched by their contributions.

Standing outside the synagogue in the heart of Chicago, I found myself marveling at the long chain of events stretching back to antiquity that made this building exist in this place at this moment.

The green sculpture you see atop the synagogue entrance is called "Hands of Peace":

The protruding part of the sculpture represents outstretched hands of a priest and inscribed on it in both Hebrew and English is the benediction taken from the Bible: The Lord bless thee and keep thee; the Lord make His face to shine upon thee… and give thee peace.

After entering into the Synagogue, one walks up a ramp:

While the exterior of the building is simple, a beautiful stained glass artwork entitled "Let there be light" greets you when you enter the sanctuary:

There is a functional logic behind both the ramp and the stained-glass window: the ramp provides wheelchair access without requiring an elevator, and the window admits softened daylight without relying on electric bulbs. Because Orthodox Jews do not use electricity on Shabbat (from Friday evening to Saturday evening), these features accommodate that requirement and embody Louis Sullivan’s “form follows function,” described in the previous post.

The history of the Jews highlights the distinction between objective reality and socially constructed reality. Objective reality exists independent of human beliefs—physical facts, natural laws, and events that remain true whether or not anyone acknowledges them. Social reality refers to things that become “real” because people collectively believe in them—nations, money, caste, gods, rights, rituals, traditions, institutions.

Consider a day in the life of a devout Brahmin priest. From dawn to dusk, he follows a routine shaped by scripture. He rises before sunrise, bathes, chants purifying verses, and tends to the household shrine with flowers and mantras he believes possess cosmic force. His day moves through rituals, blessings, and the careful observance of inherited rules that guide each choice. At night, he returns to his texts, convinced that his actions help uphold the world’s order.

The Brahmin priest's world is entirely real to him. Similarly, to a devout Jew, Abraham and Moses are real people. For the believing Christian, archaeological evidence of the historical Jesus is a bonus but not essential to his reality. Ukrainians’ identity as a people distinct from Russians is today a socially constructed reality, regardless of what historical maps may have been.

In the "post-truth" society of the current moment, we are understandably suspicious of socially constructed reality. Yet, as Yuval Harari argues, humanity’s ability to believe in “fiction” is a superpower. He points out that the line from the American Declaration of Independence—all men are created equal—is objectively false. In nature, certain truths hold—gravity pulls organisms toward the earth, offspring inherit genetic traits from their parents—but there is no biological law that renders all humans equal at birth.

And yet, when millions believe in that “fiction,” a socially constructed egalitarian reality produces objectively real consequences: the abolition of slavery, universal adult suffrage, and same-sex marriage.

Conflict arises when groups differ on what they consider objective fact versus socially created meaning. The Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, for instance, represented an objective reality of a physical building . It was vandalized by Hindu pilgrims because it clashed with their socially constructed reality that the mosque stood on the birthplace of Lord Rama. The Palestinian conflict mirrors this dynamic.

In such schisms, each side attempts to show that its own reality is not merely socially constructed but objective. Archaeological or documentary evidence is marshaled—of a buried temple, of Jewish settlements in antiquity, of Ukraine’s “integral” status within Russia. But these disputes are hard to resolve in any lasting way until the opposing sides can build a new shared socially constructed reality. France and Germany were historic enemies with incompatible national myths. But after World War II, they constructed the shared supranational "imagined reality" of a united "Europe".

The accident of our birth largely determines the socially constructed realities we inhabit. We do not choose our nationality, religion, or social milieu. In time, many of us become part of a socially constructed reality ourselves, reflecting the expectations of our reference group. Human life is, in many ways, a process of unknowingly internalizing socially transmitted dispositions—values, ambitions, tastes—and, if we are fortunate, recognizing which of them do not align with our own joy. If we are luckier still, we learn to let them go.

The National Building

Further south from the synagogue stands the Commercial National Bank Building at 125 South Clark:

In the picture above, you can see the building’s tripartite composition—a narrow base, a middle section marked by grand pillars, and an upper segment with arched windows just below the roof.

The Commercial National Bank—one of Chicago’s oldest financial institutions—began operations in 1865. By the early 1900s, it had grown so successful that a new headquarters was commissioned, and the building opened on May 1,1907. Its design follows the principles of "classical revival architecture" evoking the aesthetic of Greek and Roman buildings of antiquity. Features displayed in the picture below such as the ornamented pillars and the sculpted reliefs along the walls lend the structure an antique appearance:

By choosing an “antique” look and feel, the architects were subtly addressing the widespread suspicion of banks’ durability at the time. Banking, like religion, is another example of Yuval Harari's fictions though here the shared delusion is not of a god in heaven but of money in the vault. The house of cards—rendered in this case as a monumental shell of terra cotta—rests on that fiction. The gravitas-laden term “fractional reserve banking” simply means that banks keep only a fraction of your deposits and lend out the rest.

The day a sufficiently large number of people grow anxious about the safety of their savings, a self-fulfilling “run on the bank” unfolds. The public’s apprehension that their money may not be in the vault is rooted in another of Harari’s fictions: the limited liability company. Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield famously declares:

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen [pounds] nineteen [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.

Failing to adhere to his own maxim, he lands in Debtors’ Prison. A modern entrepreneur, however, can pay the state a modest fee to conjure into existence a fictional entity—Micawber LLC—in which he is not personally responsible for the company’s debts. By the time the LLC files for bankruptcy, the only asset this imagined entity may hold is the fabricated lunar real estate it bought with the bank loan.

The architects wanted the National Building to project a sense of perpetuity at a time when bank failures were common. While banking has become safer, the underlying need to subtly shape perceptions in order to sustain fictions is timeless. Companies use the trappings of “family”—holiday celebrations, pep talks, office photos—to mask the fact that belonging can end the moment a building badge is deactivated. The brutality of war is sold with the language of duty and banners of glory.

The Commercial National Bank occupied the building for less than a decade. In 1914, after merging with Continental Bank, the institution moved to a new headquarters. The building, now renamed the Edison Building went on to serve for more than five decades as the headquarters of Commonwealth Edison—ComEd—the electric utility that serves Chicago.

Anyone who has lived in Chicago knows the ComEd bill; it is the city’s sole electricity distributor. But it was not always so. When the company’s founder, Samuel Insull, arrived in Chicago in 1892, he found dozens of small firms selling electricity. He began buying them out and consolidating their networks, gradually transforming electricity distribution into a monopoly.

Insull was competing not only with rival electric providers but with an entirely different energy system. Up to the mid-19th century, streetlights relied on the same flame technology people used at home—candles and oil lamps that cast only small, flickering pools of light. Beginning around 1850, gas generated from burning coal and delivered through underground pipes illuminated streets and homes.

Edison’s light bulbs were a major improvement over gas-lit indoor lamps, which produced smoke and soot. By the late 19th century, electric companies had adopted a model similar to that of the gas companies, generating power in central stations and distributing it to customers in the surrounding neighborhoods. ComEd’s Fisk Generating Station—now in a decommissioned state within the Pilsen neighborhood—entered service in 1903 and housed the largest generator of its time:

Source: Library of Congress

In the battle between the two energy systems, electricity had an unlikely ally—or should I say, alley:

The alley system of Chicago was built into the city’s design from its incorporation in 1837. By then, alleys had become standard in North American town planning—a benefit New York lacked because it was laid out earlier. Alleys have long been a boon to Chicago: they handle trash pickup, provide secondary access, and serve as entryways for garages. Manhattan, by contrast, often reeks at night because garbage is left on the curb for pickup.

These alleys also served the electric utilities by hosting overhead wires, keeping the main streets both safer and aesthetically appealing. Gas, by contrast, was carried into homes through underground pipes, but electricity—because of technology limitations of the time—had to travel by overhead lines.

The two systems coexist today. In the various apartments I lived in across Chicago, the HVAC and washer–dryer ran on gas, while the lighting, dishwasher, and refrigerator were electric; the cooktop could go either way. While the gas piped into American homes today is almost entirely natural gas, incredibly a non-trivial share of the electricity is still produced from coal.

I imagined Chicago’s municipal workers igniting streetlamps by hand before piped gas—and later electricity—became available. Even street lighting, let alone home illumination, would have been a luxury then. Today Chicago's neighborhoods are known for their iconic streetlights:

Improbably, the spread of lighting in Chicago provoked moral outrage. In 1909, Samuel Wilson Paynter published Chicago by Gaslight, in which he railed against the moral decay of the city’s emerging nightlife:

I have witnessed young boys and girls in their tender years, reeling, staggering drunk, going and coming from vile dens (so-called concert saloons) and not a hand raised to stay their downward career. I have seen mothers with tears streaming down their sunken cheeks, eyes swollen from weeping tears of blood, stand in front of these devil-dealing places, pleading with their children to return to their home.

Those who worry about the dangers of social media, the internet, or AI today may be surprised to learn that Jonas Hanway, an Englishman of the 18th century, was physically attacked for daring to walk through London with an umbrella—a relatively new innovation then associated with French noblewomen. His assailants were drivers of horse-drawn carriages, whose services were in brisk demand, much like Ubers today, whenever it rained.

It is easy, of course, to laugh at medieval hansom drivers and puritan scolds. But a wise man once reflected on the perils of writing—an activity so ubiquitous today that we do not think of the alphabet as technology. He recounts the myth of the Egyptian god Theuth presenting his invention—writing—to King Thamus, praising it as a cure for forgetfulness that would make people wiser. Thamus disagreed, warning that writing would erode memory by encouraging people to rely on external symbols over their own recollection.

The wise man who concurred with Thamus was Socrates. Unfortunately for him, Plato wrote this down in "Phaedrus", subjecting Socrates to our ridicule—a fate worse than hemlock, some would say. Ha!

Energy enables technological development, but the technologies that actually emerge depend on human needs, available resources, scientific knowledge, economic incentives, ethical norms, and environmental constraints. When Samuel Insull was electrifying Chicago, he could not have imagined the machines and gizmos electricity would one day animate. This limitation of human imagination leads to a dilemma faced by scientists searching for technosignatures of alien species: we cannot conceive of what “advanced” technology might look like to them, just as an undiscovered island tribe on earth would not know to scan the distant sky for planes.

The Russian scientist Nikolai Kardashev addressed this dilemma by proposing a framework that ranks a civilization’s technological maturity by the total energy it can harness and use. Although we consume far more energy today than when Chicago was first being lit by gas and electric companies, we still have not reached even Level 1 on the Kardashev scale. At Level 1 is a planetary civilization that can harness all the energy available on its home planet. That includes most of the energy from its parent star (the Sun in case of Earth) that reaches the planet as well as every natural terrestrial source—wind, hydroelectric power, fossil fuels, and more.

Level 2 marks a stellar civilization able to harness the full energy output of its parent star (Sun in our case), not just the portion that reaches the planet. Achieving this would demand a colossal engineering structure encircling the star to capture its radiation output. Level 3 describes a galactic civilization that taps the energy of its entire galaxy—hundreds of billions of stars. For us, that would mean capturing the energy not only of the Sun but of every star scattered across the Milky Way.

A sidebar about Samuel Insull, ComEd’s founder, is his involuntary contribution to cinema. Insull—once Thomas Edison’s private secretary and later a key executive in Edison’s sprawling business empire—came to Chicago after being passed over for the top job at General Electric. He commissioned the Civic Opera Building on Wacker Drive and closely oversaw its design:

Source: Library of Congress

Insull had married the much younger actress Gladys Wallis, who, after more than two decades away from the stage, returned briefly for a charity revival of a play. This episode was woven into Citizen Kane, which blended aspects of Insull’s life with those of its primary inspiration, William Randolph Hearst. Pauline Kael, in her New Yorker essay “Raising Kane,” suggests that the studio even tried to persuade the chagrined Hearst empire that the film might have been based on Insull. One might even say the filmmakers were adding Insull to injury!

Bankers Building

South of the National Bank Building stands the Banker’s Building—also known as the Clark Adams Building—at 210 South Clark:

Look closely at the photo above and you’ll notice that the building narrows as it rises—like a wedding cake. Architects call this a "setback"—each step in the profile where the upper floors pull back from the ones below. In the Bankers Building, you can see this clearly: the first major setback occurs where the two side wings end, and the second appears at the next roofline, above which the central tower continues upward. The reason for this design was Chicago's first zoning regulation passed in 1923, four years before the Bankers Building opened for business. One of the rules required buildings to be shaped such that light and air could reach the streets below.

New York inaugurated the practice of citywide zoning in 1916, prompted by the completion of the Equitable Building the previous year:

Source: Library of Congress

The building, named for the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States—the insurance company that owned the property—sparked an outcry because it cast massive shadows over the surrounding streets. In response, the city adopted zoning regulations to prevent future buildings from overwhelming their neighborhoods. One such rule required tall structures to “pull back” their upper floors in stages at mandated heights—the so-called setbacks. Chicago included a similar provision in its 1923 zoning ordinance.

Most countries do not recognize an explicit “right to sunlight” the way they safeguard free speech or habeas corpus. Instead, access to light is protected indirectly through zoning rules, building codes, and judicial decisions. In New York City, for example, every habitable room must have an exterior window in addition to meeting setback requirements. Japan’s notion of nisshoken likewise reflects a homeowner’s interest in receiving adequate sunlight, though it offers no formal guarantee.

An exception to this implicit system of rights is the Law of Ancient Lights in the UK. In the 16th century, sunlight was precious: candles and oil lamps were costly, dim, and prone to causing fires. A neighbor erecting a taller structure beside your home was therefore more than a mere irritation. As cities grew denser, disputes over blocked light became common, and courts held that anyone who had enjoyed uninterrupted sunlight through a particular window since “time immemorial” could claim a legally protected interest in that light. Homeowners sometimes posted signs reading “Ancient Lights” above their windows to signal their intention to defend that right against neighbors and developers.

The codification of a right to sunlight in the Law of Ancient Lights is another instance of Harari's fictions—a legally constructed one, much like the Limited Liability Company. The British courts relied on yet another fiction when granting this right: time immemorial. In 1275, King Edward I issued the Statute of Westminster, which, among many provisions, required that anyone claiming a land-related right based on long-standing custom—whether grazing privileges on common land or private ownership of a parcel—prove that the right existed as of July 6, 1189.

Before that cutoff, a claimant had to trace title back to 1066, the year of the Norman Conquest—the legal reset point for all English land. William the Conqueror, the first Norman king, asserted ultimate ownership of the entire realm and re-granted it under a new feudal order, so any later claim was valid only if it could be linked to a post-Conquest grant. By the 13th century, however, producing records from two centuries earlier had become impractical. Edward therefore chose, somewhat arbitrarily, the date his ancestor ascended the throne. July 6, 1189 marks the boundary: time immemorial ends and legal memory begins.

In 1832, Parliament revised the doctrine, reducing time immemorial to a 20-year period—meaning a homeowner now needed only to show that a window had received sunlight for two decades to assert the Right of Ancient Lights!

What is your personal time immemorial—the earliest point at which your memories rise above mere haze? You might even decide that a few drunken episodes should fall within that definition.

One man's meat is another man's poison. One man's shade is another man's shadow. The City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) Technical Manual, which governs the environmental review of proposed development projects defines shadow as "a condition that results when a building or other built structure blocks the sunlight that would otherwise directly reach a certain area, space, or feature." Lest people start protesting planting of trees it clarifies that "the shade created by trees and other natural features is not considered to be shadow of concern for the impact analysis".

In Japan, nisshoken—the right to sunlight—coexists with komorebi, a term that literally means “tree-filtered sunlight.” It describes the play of light and shadow created as sunlight slips through the gaps between leaves and branches.

Source: Pixabay

Beyond its literal meaning, komorebi carries cultural significance in Japan, evoking the quiet pleasure of noticing nature’s subtle beauty in everyday life. In Perfect Days, the protagonist Hirayama’s nearly identical park photographs—each distinguished only by a slightly different play of komorebi—reveal the same fine-grained attentiveness that allows him to spot the tiny, easily overlooked details in the toilets he cleans.

The tension between our responses to shadow and shade arises from the gap between geometry and experience. Zoning and building codes regulate shapes and dimensions, while humans register feelings. Yet zoning, in its own quiet way, was also a means of managing how people felt. Zoning in the United States has a fraught history as a tool of racial exclusion.

Cities often reserved entire districts for single-family homes with mandatory minimum lot sizes, ostensibly to preserve low density. Though outwardly race-neutral, these rules effectively barred Black residents, who could afford only apartments in multifamily buildings. Land bordering Black neighborhoods was frequently zoned for industrial use, ensuring that the privileged were spared the pollution. The Equitable Building set in motion a practice whose consequences proved anything but equitable!

Above the Clark Street entrance of the Bankers Building sits a prominent relief sculpture:

At the center is a hemisphere showing North America, marked with the building’s completion year—1927—and a star within the map identifying Chicago. To the left stands Vulcan, the god of fire and artisans, hammer in hand; to the right is Hermes, the god of commerce. In the context of the Bankers Building, the sculpture signals the interdependence of banking, embodied by Hermes, and industry, embodied by Vulcan. The notion that virtue lies in a direct link between the physical and financial worlds echoes today’s Main Street–versus–Wall Street rhetoric. The sculptor of this relief would likely be dismayed by how that relationship has evolved.

Consider a farmer who signs an agreement with a grain buyer months before harvest, locking in a price of $5 per bushel. When harvest arrives and the market price hits $6, he forfeits the extra dollar—but he doesn’t mind. The contract gave him peace of mind while planting and tending his fields. In this arrangement, both parties physically handle the wheat.

Now enters a banker from Frontier Bank who, like the grain buyer, agrees to pay $5 per bushel. At harvest, the farmer sells his wheat on the spot market for $6 and pays the banker $1; if the spot price were $4, the banker would pay the farmer $1. The banker never touches the wheat. He is simply wagering on its future price in hopes of making a profit. On winning bets, he collects from the farmer; on losing bets, he pays out. Here, only one party—the farmer—ever touches the wheat.

The Frontier Bank dude proves remarkably good at predicting wheat prices and earns handsome profits by signing similar contracts with thousands of farmers. Envious of this success, competitor Valley Bank jumps into the same business.

Eventually, Frontier Bank and Valley Bank reach opposite conclusions about where wheat prices are headed. Frontier expects prices to rise; Valley anticipates a decline. They strike a wager with each other. At this point, neither side of the trade ever touches a single kernel. Hermes is severed from Vulcan. Voilà!

N-S Street 5: Dearborn Street

Manhattan Building

Done with Clark Street, I walked north along Dearborn, pausing to gaze at the Manhattan Building at 431 South Dearborn:

This 16-storey building opened in 1891 and is among the oldest surviving structures in the city. At the time of its construction, it was Chicago’s tallest. One major concern for its architect, William LeBaron Jenney, was the impact of wind loads on the frame. The engineering measures he introduced to wind-proof the structure were considered innovative for their time.

When the Manhattan Building was going up, the need to prevent tall buildings from excessive sway through support systems was only beginning to be understood. You may be alarmed to learn, however, that skyscrapers are designed to sway slightly. In strong winds, some can move as much as six inches in either direction.

Anyone who has been to Chicago—especially one who has walked near the lakefront—intuitively understands its reputation as the “Windy City.” Surprisingly, the moniker may also allude to the alleged braggadocio of its residents, who were said to be full of “hot air.” In the nineteenth century, civic leaders in other American cities dismissed Chicago’s claims to greatness as delusional. The term was used in both its literal and figurative senses, the latter functioning as a nifty pun.

However, much like the tale of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow causing the Great Fire, another urban legend that refuses to recede is the claim that Charles Alexander Dana, editor of the New York Sun, coined the epithet in 1890 after Chicago beat New York for the right to host the World’s Columbian Exposition—a big international fair held in 1893 to mark the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. While Native Americans arguably had greater reason to be peeved, it was Dana who peppered his newspaper with many insults—yet “Windy City” was not one of them. He must have had a lot of time on his hands because he wrote a full-page diatribe, titled Chicago as Chicago Is.

Luckily for Chicago, the World’s Fair of 1893 was a resounding success, proving that the city could reinvent itself after the Great Fire:

Source: Library of Congress

Charles Alexander Dana was not the only writer to speak scathingly of Chicago. Rudyard Kipling, upon visiting the city in 1889, wrote:

I have struck a city—a real city—and they call it Chicago. Having seen it, I urgently desire never to see it again.

Ouch!

Kipling was repelled by the capitalist hustle he saw. To illustrate his point, he evokes life in a small Punjabi village through four figures: a Changar woman who winnows about seventy bushels of corn a year; Purun Dass, the moneylender extending modest loans; Jowala Singh, the smith repairing village ploughs; and Hukm Chund, the letter-writer circulating news and gossip. He then contrasts them with their counterparts in Chicago, where the same activities—processing grain, lending money, manufacturing tools, and transmitting information—occur on a vast industrial scale.

Kipling’s idealization of the “noble savage” is a privileged indulgence, mistaking hardship for authenticity because he did not have to bear its weight. Had Isser Jang been industrializing in 1889—the year of his visit—as rapidly as Chicago, the descendants of the Changar women, Hukm Chund, Jowala Singh, and Purun Dass would likely be living in a first-world country today. Kipling was indulging in what Rob Henderson, writing in the New York Post, calls a “luxury belief”—ideas that confer status on elites while imposing costs on those below them.

Kipling also sneers at a cab driver who was showing him around:

He conceived that all this turmoil and squash was a thing to be reverently admired, that it was good to huddle men together in fifteen layers, one atop of the other, and to dig holes in the ground for offices.

He was spared a sixteenth layer only because the Manhattan Building opened in 1891—two years after his visit. Observing the Dearborn Street façade, you can see three horizontal layers: the glass storefronts at the base, the two storeys in the gray band above, and the warm brown upper floors:

The emphasis on the horizontal orientation was likely meant to reassure a public still unaccustomed to skyscrapers. Strangely, given that the architect was presumably aiming for a calming effect, he also incorporated menacing faces along the windows—grim visages awaiting any pedestrian bold enough to look up:

As things turned out, William LeBaron Jenney need not have worried much about public unease over tall buildings. We have come a long way since then. Today, the title of “world’s tallest building” is a coveted prize.

In the summer of 1929, Manhattan became the stage for a fierce “race for the sky.” Walter Chrysler, the automobile magnate, squared off against the Bank of Manhattan Trust in a contest to erect the world’s tallest building. By spring 1930, the bank seemed poised to prevail—until Chrysler’s team hoisted a slender spire through the building’s crown, snatching the title at the last moment:

Picture: Spire of the Chrysler Building

Source: Library of Congress

The Chrysler Building would lose the title to the Empire State Building within a few months, but the competition to build the world’s tallest has not stopped. The term vanity height refers to the distance between a skyscraper’s highest inhabitable floor and its pinnacle. The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat—the arbiter of height rankings—introduced criteria in the early 1970s that counted the vanity height. In doing so, it codified a practice that has sparked recurring controversy. In 1998, the 88-storey Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur became the world’s tallest, beating Chicago’s 108-storey Sears Tower. An astonishing 29 percent of Dubai’s Burj Khalifa is vanity height.

Of course, height padding is not limited to architects and developers. A study by Northwestern University found that people overstated their height by an average of 0.33 inches on their dating profiles, with men being the more frequent offenders. The study was conducted in 2007, when online dating was still in its infancy. Today, you are lucky if a Bumble date doesn’t end with your body being sliced into thirty-five pieces. I love you to pieces, indeed.

Plymouth Building

Right next to the Manhattan Building is the eleven-story Plymouth Building that opened in 1899 at 417 South Dearborn:

A close look at the above picture reveals a brick upper façade resting on a base of gray terracotta. Late–nineteenth-century Chicago architects favored terracotta over brick because it allowed them to clothe modern buildings in classical reliefs, often drawn from Greek and Roman mythology, lending these new structures an air of timelessness.

In the case of the Plymouth Building, the terracotta cladding at the base was added in 1945, when La Salle Extension University (LSEU) moved in and made it its headquarters for more than three decades. LSEU was a long-distance learning company selling “correspondence courses” before it shut down in 1982. The terracotta addition was intended to project gravitas, countering the stigma then attached to long-distance education.

The remote learning industry received a major tailwind in 1863, when the United States Post Office abolished distance-based letter rates and introduced home mail delivery; until then, recipients had to collect letters from local post offices. Causality that unfolds contemporaneously—between the internet and online learning, for example—feels intuitive in a way that older chains, linking postal policy to long-distance education, do not. Schopenhauer noted that the perception of causality, like that of time and space, is a marker of human intelligence. Yet our causal inferences are constrained by cognitive limits. The postal-policy example illustrates one such constraint: recency bias.

Imagine a world in which AI could reveal the full chain of causation behind everything we encounter, stretching back to antiquity.

In such a world, we might cling less tightly to traditions and inherited identities like religion, even if we continued to practice them out of habit. Path dependence, described in the previous post, would seem to vanish. Such technology would undermine the case for conservatism, one of whose guiding principles is to err on the side of conserving traditions precisely because we do not know the interconnections that hold the social order together. From this perspective, a conservative would argue that Hong Kong’s phased path to independence was preferable to the abrupt “freedom at midnight” that led to widespread bloodshed.The availability of such knowledge would replace prudence with perceived understanding, encouraging action where conservatism counsels restraint.

What would the look-back period of this AI be? Time immemorial, of course. And before that? For those eras, we could retreat into our socially constructed reality on Twitter. Ha!

A second cognitive limitation to the perception of causality is linear thinking. We struggle to anticipate second-, third-, or fourth-order effects of change. In 1902, a young engineer joined the Buffalo Forge Company, a New York manufacturer of industrial machinery. A client—a printer—complained that humidity was degrading the output of his presses. The engineer’s solution led to the invention of air-conditioning; the cooling was merely a by-product of dehumidification. His name was Willis Carrier. The author Steven Johnson has argued that air-conditioning later enabled the migration of conservative retirees from the North to the South, helping Ronald Reagan win the presidency—a hundredth-order consequence, perhaps, of a technical fix to a printer’s problem! We can also draw a line from the mass production of mirrors during the Industrial Revolution to Time magazine’s 2006 Person of the Year—You—literally framed by a mirror on the cover.

Successful entrepreneurs excel at anticipating second-, third-, and fourth-order effects. Most people can infer that GLP drugs will reduce demand for gyms and fast food. But consider a longer hypothetical chain. GLP-1 users find fasting easier. Religious fasts lose their difficulty premium. The moral signal of self-denial weakens. Communities begin to emphasize different virtues to signal commitment. Practices such as sweat lodges and barefoot pilgrimages—where bodily strain is the medium through which meaning is transmitted—gain appeal.

The big difference between the air-conditioning story and the GLP-1 chain sketched above is that the latter has not happened, and we do not know whether it ever will. We can distinguish between the two using a framework developed by national-security expert Gregory Treverton and popularized by Malcolm Gladwell. Treverton makes a distinction between puzzles and mysteries. Osama bin Laden’s whereabouts, Gladwell explains, were a puzzle: the answer existed, but the necessary information was missing. What would happen in Iraq after Saddam Hussein’s overthrow was a mystery—there was no hidden fact to uncover, only an outcome that would reveal itself through events.

Future causality is a mystery; past causality is a puzzle. After all, who could have predicted in advance that the convergence of the internet, cloud computing, mobile phones, and GPS would give rise to Uber? Only Travis Kalanick!

Old Colony Building

The Plymouth Building is a minion, sandwiched between two taller and wider structures.

Source: Library of Congress

In the image above, the Plymouth sits at the center, the Manhattan to its right, and, on the left, the seventeen-storey Old Colony Building, completed in 1894, at 407 South Dearborn :

The name of the building derives from the two reliefs on either side of the Plymouth Street entrance pictured below:

The engravings in the above picture are a replica of the seal of the "old colony" Plymouth—a colony of historic significance in American history.

In the early 1600s, a group of religious nonconformists inspired by the 16th century protestant reformer John Calvin deplored the hierarchy and corruption of the Church of England and the Catholic Church. They wanted a simpler and unmediated experience of religion but were persecuted in England for their religious beliefs. A group of these "pilgrims" set out on the Mayflower for the New World in September 1620.

As one would expect from Americans, these intrepid adventurers adopted the tools of capitalism to facilitate this journey. First they established a revenue source by obtaining settlement rights to land within the jurisdiction of the Virginia Company, a British enterprise similar to the East India Company, engaged in establishing colonial outposts. Then, they raised money from a consortium of London businessmen effectively "securitizing' the future land-based revenues derived from fur, timber and fish. The pilgrims' faith supplied purpose. Capital supplied passage. Apparently doing God's work needs venture capital!

The Pilgrims intended to land in Virginia but were blown north to Massachusetts by storms and navigation errors. Columbus landed in the wrong hemisphere and insisted he was right; the Pilgrims landed in the wrong colony and insisted that their contractual commitments with the Virginia Company were not valid. In late December, the Mayflower anchored at Plymouth Rock, where the Pilgrims established the first permanent European settlement in New England. Despite losing more than half their number in the first brutal winter, the survivors built a largely self-sufficient economy within five years.

At the time the Pilgrims established their settlement in Plymouth, two types of colonies existed: charter colonies, run by private companies such as the Virginia Company, and royal colonies, administered directly by the Crown. Plymouth was neither. It functioned as an independent colony until 1691, when it was absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which did operate under a royal charter. Despite this legal ambiguity, Plymouth’s leaders assumed the full duties of civic authority. They passed laws, issued land deeds, and negotiated treaties, grounding their legitimacy in a social contract articulated in the Mayflower Compact:

Picture: Signing of the Compact in the Cabin of the Mayflower

Source: Smithsonian Museum

The image below shows a close-up of the seal they created in 1629—nine years after the colony’s founding—as engraved on the Old Colony Building:

The seal shown above depicts four Native American figures, each kneeling within a quadrant of St. George’s cross, the symbol of England. Each holds a burning heart—the emblem John Calvin used to seal his letters—signifying the offering of one’s heart to God. The seal also records the colony’s founding year and bears the prosaic Latin motto Sigillum Coloniae Plymouth Novae Angliae, meaning “The Seal of the Colony of Plymouth in New England.”

The inclusion of Native Americans within a symbol of colonial authority can read as gratuitous mockery of the conquered. More likely, it was meant to frame colonization as a moral gift, implying that evangelization compensated for dispossession. Where Kipling venerated the noble savage, the Pilgrims fixated on the savage part.

Seals in the Plymouth era were made by hand-cutting a design into metal and pressing it into melted wax placed on a document. The symbolism of solid metal impressing itself onto molten wax is potent. The triad of metal, wax, and imprint is fertile ground for metaphor because it separates three things we often conflate: the substrate that exerts force (metal), the medium that receives it (wax), and the form that persists after contact ends (the imprint).

Political revolutions can be read through this lens. Metal is institutional power—office, crown, law. Wax is society’s consent. The imprint is legitimacy. History is crowded with moments when rulers mistook the presence of metal for the continued softness of wax. The clearest example may be the dissolution of the USSR. The Soviet state retained immense institutional power—party, police, military, bureaucracy. What disappeared was belief. When pressure eased under Gorbachev, the system collapsed. The wax had cooled decades earlier.

Buddhist thinkers use the same triad to explain rebirth. Metal represents the solid external trappings of biological life; wax, mind which in Buddhism is not a creation of the brain; the imprint, the mental proclivities formed by lived experience. Unless one attains nirvana, each new life leaves further imprints on the wax. Contrary to popular depictions of reincarnation, Buddhist thought holds that it is not an individual who is reborn, but these accumulated imprints of mind. Ever since I heard Joseph Goldstein put it pithily—“what is reborn are your neuroses”—I have found it useful to think of life as a laundromat, where one strives to scrub away unskillful imprints for one’s reincarnated progeny.

The three buildings on this stretch of Dearborn Street—the Manhattan, Plymouth, and Old Colony—along with the Monadnock Building on Jackson Boulevard, sit at the overlap between the Loop and Printers Row which is a designated National Landmark District. These buildings once housed printers, publishers, bookbinders, and paper merchants well into the mid-twentieth century. Though these skyscrapers were built after the Great Fire of 1871, the printing trade had congregated here long before it.

The story of Printers Row begins on November 16, 1833, when John Calhoun published the inaugural issue of Chicago’s first newspaper, the "Chicago Democrat", from this corner of the city. The paper reportedly launched with 147 subscribers—a modest number until one recalls that Chicago’s population that year, when it was incorporated as a town, stood at just 500. By 1837, when the population had surged to 8,000 and Chicago was reincorporated as a city, three additional newspapers had entered the fray.

In 1836, Calhoun entered public office and handed the paper to John Wentworth, who ran it while also serving in Congress. In 1861, alarmed by the outbreak of the Civil War, Wentworth sold the paper to the "Chicago Tribune", bringing the city’s oldest newspaper to an end. It may have been a poor calculation: the war soon triggered a sharp rise in newspaper readership.

Partisan fury at the press, often assumed to be a modern affliction, has deep roots. In September 1836—just three years after Chicago got it's first newspaper—another Illinois town saw the launch of the "Alton Observer". Its publisher, Elijah P. Lovejoy, a white abolitionist minister, had already faced violent opposition in St. Louis, Missouri, for his views. He crossed the Mississippi to Alton, expecting a warmer reception in a free state. Instead, pro-slavery residents dumped his printing press into the river as their welcoming gesture.

Lovejoy initially reassured the town that his opposition to slavery was a personal, religious conviction and that he was not an abolitionist. He soon reversed course, acquired a new press, and began publishing explicitly abolitionist arguments. In August 1837, a mob destroyed this second press. A third met the same fate upon arrival. When a fourth press reached Alton in November 1837, a mob attacked the warehouse where it was stored. Lovejoy was killed in the assault.

Picture: a printed copy of a sermon given by Rev. David Root at the memorial of Elijah Parish Lovejoy in 1837

Source: Smithsonian Museum

In the digital age, it is no longer intuitive to us that the “press” in freedom of the press once referred quite literally to the equipment itself.

Fisher Building

Adjacent to the Old Colony, separated by an L station, stands the Fisher Building at 343 South Dearborn:

The building’s bright orange terra-cotta exterior is a welcome departure from the gray that dominates much of Chicago’s skyline.

The Fisher Building opened in 1896, after its neighbors—the 16-story Manhattan Building (1891) and the 17-story Old Colony Building (1894)—were already complete. Eager to raise the stakes, the architects pushed to eighteen stories. By then, the city had grown uneasy about the safety of tall buildings and, in 1893, imposed height restrictions. The Fisher was allowed to proceed only because its permit predated the ordinance. In the decades that followed, Chicago gradually relaxed these limits, ultimately abandoning fixed height caps in favor of setback requirements under the 1923 zoning ordinance mentioned earlier.

Picture: from left to right: Fisher, L train line, Old Colony, Plymouth, Manhattan

Source: Library of Congress

City governments indirectly regulate building height through the Floor Area Ratio (FAR), also known as the Floor Space Index (FSI). This is the ratio of total floor area to lot size. An FSI of 2, for instance, permits 4,000 square feet of built space on a 2,000-square-foot plot. Skyscrapers become viable only when the permitted FSI is exceptionally high.

When Chicago debated permissible heights in the nineteenth century, safety was the overriding concern. By the time the 1923 zoning regulations were introduced, aesthetic considerations—especially access to sunlight—had moved to the fore. Today, some urban planners oppose tall buildings for a different reason altogether: the congestion and strain on local utilities that accompany extreme density. Skyscrapers often exemplify Lance Pritchett's isomorphic mimicry where governments aspire to make their cities resemble Manhattan without investing in the infrastructure—public transport, water systems, electricity—that makes such density workable.

Others object to tall buildings on philosophical grounds. They argue that life on higher floors distances people from the theater of humanity unfolding at street level, dulling everyday empathy. I recall train journeys from my childhood, watching fragments of lives through open windows of homes lining the tracks and wondering about the people inside. Jan Gehl defines human scale as streets and buildings designed so that a person walking at a normal pace can see faces, read shop signs, feel safe crossing the street, and visually absorb their surroundings. This concern is not merely an urban-elite romance. Slum dwellers relocated to high-rise towers often report emotional distress at the loss of their former horizontal, community-based habitat.

Logically, we should live in habitats we are evolved for. The problem is that we are evolved for a way of life completely different from the one we live. The earliest known fossils of Homo sapiens, dating back roughly 300,000 years, were discovered at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. The shift from hunter-gatherer life to settled agriculture began only about 12,000 years ago. In other words, at least 95 percent of human existence was spent foraging.

There is a growing movement to design aspects of modern life around hunter-gatherer patterns: restaurants that grow their own produce, community vegetable gardens visible from the sidewalk, and the desire paths described in the previous post. The paleo diet follows a similar logic, favoring foods that would have been directly available to hunter-gatherers—meat, fish, fruits, nuts, and roots. These are voluntary choices made by people who have run out of things to spend their money on.

Most people striving for a higher economic standing signal affluence differently: big SUVs, large homes, and warehouse-sized refrigerators stocked through Costco runs. American-style consumerism is not an aberration; it is the predictable outcome of the development process.

Strangely, there may be one element of hunter-gatherer life that futurists believe is close at hand. The anthropologist James Suzman spent decades studying Bushmen in southern Africa who still live by foraging. The group he studied devoted only thirty-six hours a week to survival—roughly split between foraging and domestic chores. The reason was simple: they did not hoard surpluses. Once they had enough for the day, they stopped. Suzman describes this condition as affluence without abundance.

Advocates of AI promise something more radical: both affluence and abundance. Within our lifetime, they claim, humans may no longer need to work to live. In such a world, even the thirty-six-hour week of the Bushmen would seem excessive.

This is not a new idea though. In 1930, in the throes of the Great Depression, a wise man writing optimistically in the essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren declared that in a hundred years the struggle for subsistence would be over and for the first time in human history, man's primary concern would be what to do with leisure. In such a world he wrote:

The love of money as a possession -as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semicriminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.

The thinker who predicted that all this would arrive by 2030 was John Maynard Keynes.

The Fisher Building is named after its proprietor, Lucius Fisher, who commissioned it. The architects, having some fun at the owner’s expense, carved engravings of aquatic creatures into the walls:

If these architects were designing a Trump Tower, they may have engraved the following:

Source: Pixabay

Beyond their shared origins in the final decade of the nineteenth century, the four buildings on this stretch of Dearborn—the Manhattan, Plymouth, Old Colony, and Fisher—have another trait in common. All were constructed for commercial purposes—offices and printing presses—and have since been converted to residential use.

The original impetus for their construction, and for the growth of the broader Printers Row district, was the opening of the Dearborn Street Station in 1885. The station served as the entry point for massive quantities of raw materials like paper and ink, and the exit point for finished books, magazines, and newspapers to be distributed nationwide:

Source: Library of Congress

The station closed in 1976 when Amtrak consolidated its operations at Union Station, after which the building was repurposed for retail and office use. Its closure was the coup de grâce to a decline that had begun in the mid-twentieth century. Highways opened up cheaper suburban land, and even before the internet, the bulky printing machines that powered Printers Row had become obsolete. As demand for commercial space ebbed, adaptive reuse—converting offices to residences—gave many buildings in the district a fresh lease on life. The issue has only grown more salient as office occupancy in central business districts across the United States has plunged since the pandemic.

Even where zoning permits it, converting office buildings into residences is rarely straightforward. One persistent obstacle is windows. A typical office floor can accommodate rows of cubicles lit by windows only along the perimeter. When subdivided into apartments, the interior portions become difficult to use because those units lack windows. Many city regulations require every habitable room to have one.

The issue of windows sparked a furor when billionaire Charlie Munger offered to fund a massive dormitory for the University of California, Santa Barbara, with one condition: it had to follow his design, which specified windowless rooms. Munger argued that eliminating windows would maximize space efficiency, allowing every student a private room. But his aim was not purely utilitarian. He believed the craving for daylight would push students out of their rooms, encouraging serendipitous encounters. Mercifully, the university dropped the proposal after a public backlash.

The building, in the billionaire's vision, would treat daylight the way casinos treat clocks—absent by design.

Flamingo

Walking on Dearborn, one comes across the "Flamingo"—a bright red huge work of public art:

Both Flamingo and the Bean at Millennium Park allow viewers to come unusually close—close enough to walk beneath them rather than merely observe from a distance. The difference lies in attitude: Flamingo asserts itself through a vivid red that clashes with the Loop’s pervasive gray, black, and steel, while the Bean adopts the city’s tones and materials, blending in by reflecting them back.

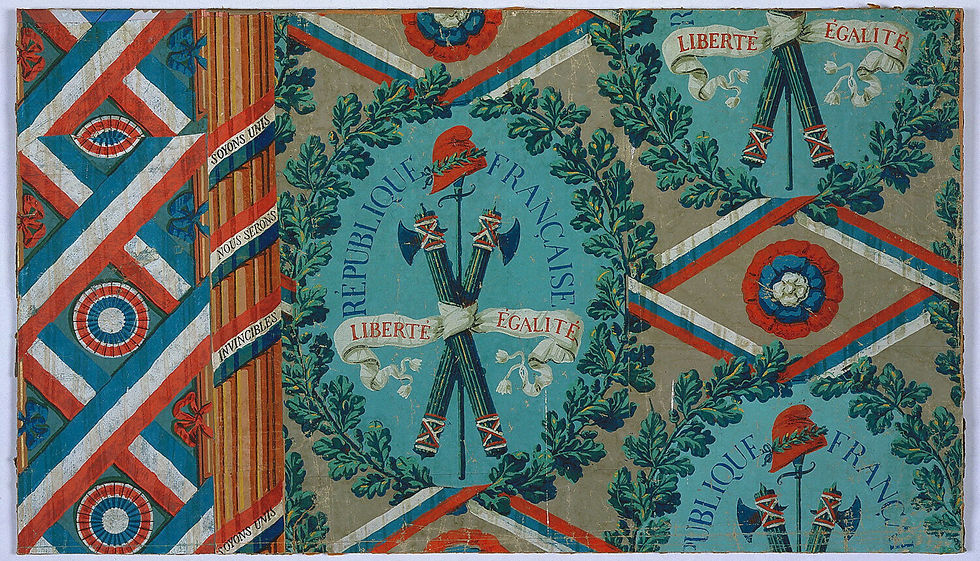

One need not be a student of art to see that sculptor Alexander Calder was using color to disrupt the architectural status quo. Color, deployed as an assertion of difference, has long been used to unsettle established orders. A famous instance occurred on 14 July 1789, when insurgents wearing blue and red cockades—the traditional colors of Paris—stormed a prison. Two weeks after the storming of Bastille, white—the color of the Bourbons—was added to form the French Tricolor. The mingling of white, a symbol of royalty, with red and blue, symbols of the people, reflected an initial hope for a constitutional monarchy. Over time, these colors came to represent the three pillars of the French Republic: blue for liberty, white for equality, and red for fraternity.

Source: Smithsonian Museum

Many historians read the tricolor’s red less as fraternity than as blood, given the revolutionaries’ penchant for brotherly decapitation.

The association of colors with revolutions continued. In the Russian Civil War that broke out in 1918, the Reds were the Bolsheviks and the Whites the defenders of the old order. In 1986, the Yellow Revolution overthrew President Ferdinand Marcos; supporters wore yellow ribbons and clothing, inspired by the song “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree.” In 2004, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians dressed in orange ushered in the Orange Revolution, which led to a court-mandated re-run of the presidential vote and overturned the original result.

For revolutionaries, color often marks a political counterpoint. The Rainbow Flag of the LGBTQ movement, by contrast, uses color to challenge inherited social norms. White became the emblem of the suffragette movement. In Buddhist traditions, saffron signals renunciation of worldly life.

The Flamingo, beyond its chromatic contrast with its surroundings, introduces a geometric dissonance as well: its twisted, curving form cuts against Chicago’s rectilinear grid.

Wrapping Up

The Earth may revolve around the Sun, but the self is the center of the universe. From that perch, four concentric circles radiate outward, enclosing it.

The first is the web of personal and professional relationships. These are people we know with varying degrees of intimacy—from those with whom we exchange small talk to immediate family. This circle has been shrinking across generations. Rudyard Kipling’s critique of Chicago’s industrial scale was patronizing, but factually accurate. The local moneylender was not better than today’s digital lender, yet he was someone you encountered socially.

The second circle consists of people with whom we share physical space—roads, power grids, and third places—but whom we do not know. We may not have signed a Mayflower Compact with them, but we are bound to them by a social contract mediated through the state. In everyday civic life, that contract surfaces when we stop at red lights for strangers, refrain from opening businesses in residential zones, and accept the authority of documents bearing the state seal.

People do move from the second circle into the first, but this happens less often now. It is increasingly possible to pass an entire day without speaking to another person—entering buildings with access cards, buying groceries at self-checkout counters, ordering food through apps, talking with customer service chatbots, and ending the evening with entertainment recommended by algorithms rather than conversations. The drift toward digital isolation feels inexorable, regardless of how many windowless rooms billionaires build or how much governments lower floor-space indices.

The third circle includes people we will never meet but with whom we share a socially constructed reality: fellow citizens bound by a flag, believers linked by scripture, partisans united by ideology, and strangers who erupt in shared joy or grief because they support the same team. This circle is expanding even as the first two contract, leaving us more intimate with abstractions—nations, gods, ideologies, teams—and less practiced at dealing with the inconvenient humans standing next to us in line. Unlike the pro-slavery zealots of Alton, we can mute discordant voices simply by retreating into online echo chambers.

The fourth circle reaches beyond Earth to intelligent life across the galaxies. We have no evidence of extraterrestrial civilizations, yet statistically it seems unlikely that we are alone. Lacking any sense of what such life might be like, we fall back on reductive measures, such as classifying civilizations by energy use on the Kardashev scale.

Life might be easier if we could see the world from the vantage point of that fourth circle, looking inward, rather than always looking out with the self fixed at the center.

Click here for Part 4 of this series.

Comments