Fontainhas, Panaji, Goa

- condiscoacademy

- Jan 6

- 30 min read

Updated: Jan 7

This essay explores the sights and sounds of Fontainhas—one of the thirty wards of Panjim, officially Panaji, the capital of Goa, where I spent four full days.

It is hard to believe that the chain of forces that brought me to a small café in Fontainhas can be traced to historical events and personalities I know only from books.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and landed at Calicut in present-day Kerala, paving the way eventually for Portuguese colonization of Goa :

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

The chain of events actually begins a decade earlier, when the King of Portugal sent Bartolomeu Dias to find a trade route to India. While the good Senhor Dias did round the Cape, discovering in the process that the Atlantic and Indian Oceans were connected, he could not venture far beyond it. His crew—hungry, short on supplies, and battered by storms—threatened mutiny, forcing him to turn back to Lisbon.

Dias named his discovery the Cape of Storms, chastened by the weather he encountered. The King rechristened it the Cape of Good Hope—a rebranding that aged far better in European capitals than in the lands it eventually opened to European plunder. Bartolomeu Dias proved that a sea route to India was possible; Vasco da Gama showed that it could be profitable; and a century later, the British demonstrated just how scalable colonial extraction could be.

Day 1

I stayed at the Mateus Hotel, located inside Fontainhas:

Like most buildings in the neighborhood, its approach is especially popular with Instagrammers:

The Hotel Mateus was originally a private residence dating to 1879, a pattern common to many commercial establishments in the area. New York–based Goan architect Jonathan Fernandes later renovated it into a nine-room boutique hotel and named it after his grandfather.

The interiors have considerable charm but lack accessibility for disabled guests and senior citizens. For those staying on the first floor, the main challenge is the staircase:

Since the history of a building or a neighborhood exists within a larger history, it is worth completing the loop of Vasco da Gama’s journey. When he landed in India in 1498, the Indian Ocean was already a thriving arena of trade linking the kingdoms of India, Africa, Arabia, and Persia. Lacking any Ricardian competitive advantage in commerce, da Gama returned to Portugal. He came back in 1502, this time with a military contingent and weapons designed to dominate sea routes rather than barter in markets.

During this period, the Portuguese violently monopolized Indian Ocean trade—sinking rivals, subduing ports, and enforcing control through an armed patrol fleet. This allowed them to buy spices cheaply in the East and sell them dearly in Europe, muscling out rival trading powers. Variants of this tactic would reappear centuries later in the actions of Somali pirates and Yemeni Houthis, with somewhat less impact—at least so we hope. With America under a MAGA administration reluctant to police the global commons, we can rest our hopes on Popeye.

Rather than building a vast inland empire in India, as the British later would, the Portuguese focused on building forts around the coast. The first was established at Cochin in 1503, with the consent of the local king, who allied with them against a regional rival. Interested primarily in commerce, the Portuguese largely avoided interfering in local governance and social customs, remaining close to their fort—an area known today as Fort Kochi.

In 1510, the Portuguese conquered Goa, battling the incumbent Muslim dynasty that had seized it in 1496. From the post office bordering Fontainhas, one gets a clear view of the Mandovi River, along which the Portuguese sailed inland to fight the battle for Goa:

Unlike Cochin, where the Portuguese established a military presence within the territory of an allied local ruler, Goa came under their direct administrative control. It is remarkable that Goa remained under Portuguese rule until 1961—more than a decade after the British had departed.

The Governor of Portuguese India, Afonso de Albuquerque, who led the conquest of Goa, also enjoys a curious afterlife in Indian culinary lore. It is widely believed that the Alfonso mango is named after him. Jesuit missionaries in Goa—when not saving souls—were experimenting with grafting techniques in the sixteenth century. One theory holds that indigenous mango varieties were soft and meant for sucking, while the Portuguese preferred firmer fruit that could be eaten with a fork. The Jesuits named these new varieties after Portuguese political and religious figures.

All this history felt very distant as I sat in the dining room of the Mateus Hotel:

The hotel stands on Rua 31 de Janeiro, a street name that marks a consequential date in Portuguese history. Portugal was a sovereign nation for most of its history, but for six decades, from 1580 to 1640, it fell under Spanish rule. On January 31, 1640, the Portuguese upper classes—who had initially acquiesced—declared independence. Like July 4, 1776, this was a declaration rather than the moment of sovereignty, which arrived only after years of conflict and eventual recognition by the defeated colonial power. By that measure, the counterparts to India’s freedom at midnight are February 13, 1668, for Portugal, and September 3, 1783, for the United States.

Fortuitously, right across my hotel is a bar:

Having checked in late, I made the only sensible logistical choice: walking straight to the bar:

Day 2

In 1984, Fontainhas was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Zone for its cultural value, celebrated as a well-preserved example of Portuguese colonial planning and architecture in India. I began the day wandering through the lanes and by-lanes of this vividly colored neighborhood:

The colors made it feel as though I were walking inside a picture postcard:

The neighborhood is teeming with bakeries and coffee shops:

One explanation for Fontainhas’s colors may lie in an unwritten colonial rule that reserved white façades for the Church. I could not corroborate this with a definitive source, but the idea felt persuasive as I found myself standing before the decidedly white Chapel of Saint Sebastian:

While the Portuguese were chiefly interested in the spice trade, any state-sponsored mercenary enterprise needs a fig leaf of idealism. Religion, as ever, supplied the moral alibi. A central figure in this justification was a man who never existed: Prester John, a mythical Christian monarch imagined by Europeans as ruling a vast, wealthy, and pious realm somewhere in the East—variously placed in India, Central Asia, or Ethiopia. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, belief in him sustained crusader hopes of discovering a powerful eastern ally who might help reclaim Jerusalem.

Two centuries later, in 1433, the Portuguese king Henry the Navigator—a devout Christian with a pronounced hostility toward Muslims—set in motion Portuguese state-backed exploration. The stated aims were twin and conveniently aligned: to locate Prester John, now believed to be in Africa, and to open a sea route to Asia. That search, animated by faith and profit alike, culminated in the voyages of Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama.

There is some archaeological evidence that Christianity may have existed in Goa before the arrival of the Portuguese. Even so, most historians agree that its prominence in the region is largely a consequence of Portuguese evangelization. Missionaries of various denominations accompanied the conquering armies, establishing churches in and around Portuguese forts. The Iberian colonial powers took religion much more seriously than their peer European imperialists.

In Goa, the earliest chapels—and associated institutions such as convents and hospices—rose on the site of the fort of the defeated Muslim rulers. Construction began soon after the Portuguese conquest in 1510. This district is now known as Velha Goa or Old Goa and served as the administrative capital of Portuguese India. Recurrent epidemics gradually emptied the area, and from 1759 onward the population shifted to Panjim, barely five miles away. In 1843, Panjim was renamed Nova Goa and formally designated the new capital.

The Chapel of Saint Sebastian before which I now stood was built in 1818. The devastation wrought by epidemics in Old Goa led to its dedication to a saint associated with healing miracles. With the next day being a Sunday, I found its doors open, congregants gathered for service:

In the picture below, diagonally to the priest’s right, is a sculpture of Christ on the cross:

Being respectful of the proceedings, I could view the artifact only from a distance, but read that it is a rare depiction of Jesus on the cross with his eyes open. The reason may lie in a darker chapter of Goan Christian history. The relic was sourced from the headquarters of the Goan Inquisition in Old Goa, established in 1560 to try heretics—especially converts suspected of secretly practicing their former faiths. The open eyes were meant as a reminder to the condemned that they were still being watched.

The Goan Inquisition itself was an overseas franchise of the Portuguese one, which expectedly has a sordid history. King Manuel I of Portugal—the patron of Vasco da Gama’s original voyage around the Cape—had, as a condition of his 1497 marriage into the Spanish royal family, agreed to expel Jewish exiles from Spain whom his predecessor had granted refuge. Neither the marriage nor the appeasement prevented Spain from annexing Portugal some eight decades later.

Although the king decreed expulsion, many Jews were forcibly converted. These so-called Novo Christians fled to Goa to escape persecution at home. In time, however, inquisitions were established in both Portugal and Goa. The Goan chapter, operating under the officious title of the Goa Tribunal of the Portuguese Holy Office, quickly widened its remit—from pursuing fleeing Jews to policing Hindu and Muslim converts, and eventually to administering religious persecution more broadly. Punishments ranged from prison, lashes, exile, and forced conversion—with execution reserved as a rarer courtesy, administered by rope, fire, or a symbolic burning when the body proved inconvenient.

Visitors arriving in Old Goa hoping to gape at something suitably ghoulish will be disappointed to learn that the headquarters was demolished by 1830, after the inquisitions were halted in 1812. In fact, by the latter half of the eighteenth century, the powers of the inquisitions—and the associated forced conversions—had already diminished considerably. For those still keen on martyrdom, blasphemy had lost its edge; only open rebellion against Portuguese rule would do. More on that later.

Adjacent to the Chapel of Saint Sebastian is a coffee shop operating out of a three-hundred-year-old villa:

I lingered over a cup of coffee, soaking in the atmosphere:

Right outside the café stands a red-brick well:

Many people online have referred to it as a wishing well but during my visit, there was no water in it and the act of throwing coins in a dry well would seem less an appeal to fate and more a quiet vote of confidence in gravity. Lest we get too scientifically minded, the two roosters you see atop the well alludes to a fantastical tale of the Barcelos Rooster.

The story exists in several minor variations, though most align with this Wikipedia version. According to a Portuguese legend, a pilgrim from Spain, traveling to Santiago de Compostela in the seventeenth century, was falsely accused of theft in the town of Barcelos in Northwestern Portugal and sentenced to hang. Protesting his innocence before the judge, he declared that a roasted rooster on the judge’s banquet table would crow as proof. The judge, indulgent or merely curious, declined to eat the bird. It proved a wise abstention: at the moment of execution, the roasted rooster stood up and crowed, prompting the judge to rush to the gallows and discover that a faulty knot had spared the pilgrim’s life. In retrospect, the judge’s finest judicial instinct may have been an unusually cautious relationship with dinner.

The legend established the rooster as a symbol of faith, justice, and good fortune in Portuguese culture. In Fontainhas, many homes display a rooster to welcome guests:

Strolling through the neighborhood I continued absorbing the sights and sounds of Fontainhas:

Hungry, I stopped by Viva Panjim, a beautiful restaurant serving Goan cuisine:

I ordered chicken chilly fry, pomfret curry and steamed rice:

I can’t vouch for its authenticity, but the food—especially the chicken—was very good. I returned another day for the fried snapper, which was excellent as well.

During my stay in Goa, I ate three versions of chicken curry, each defined by a distinct core sauce: vindaloo with vinegar and red chillies, cafreal with cilantro, and xacuti with grated coconut and coconut milk. Those with a moderate tolerance for heat would do well to check with the chef.

Goan vindaloo traces its lineage to the Portuguese carne de vinha d’alhos—literally “meat of wine and garlic,” a phrase far less incendiary than its Goan descendant of vinegar and red chillies. Even this Goan version has evolved over time. The original was made with pork and contained no potatoes, the latter likely introduced through a misunderstanding of the Portuguese alhos (garlic), mistaken for aloo.

Energized by the meal, I walked around some more. Beyond the vivid colors and the windows, a defining feature of the buildings is their balconies—some broad terraces running the full length of the house:

Others are smaller, projecting out onto the street:

A third, less common configuration was a porch that set the home back from the street:

While the configuration in photo above is rare in Fontainhas—where limited space pushes homes right up to the street—outside Panjim, in Goan villages, almost every house I saw had a balcao:

From the writings of Goan authors, I learned that balcaos functioned as a social device, allowing neighbors to drop in for gossip without the formality of being invited into the house.

One common sight was blue-and-white nameplates:

In the early sixteenth century, King Manuel I of Portugal became enamored of the Islamic tilework he encountered in Spain and adorned his palace with azulejos—a term derived from an Arabic word meaning “polished stone.”

The rest of my day passed in unhurried meandering through the neighborhood.

Day 3

The neighborhood of Fontainhas sits at the foot of the Altinho hilltops:

The name Fontainhas literally means “little fountain,” a reference to a natural spring that once flowed through the area. In the late eighteenth century, a Portuguese aristocrat, Antonio Joao de Sequeira, arrived in Goa and established a private coconut plantation here, naming it Palmar Ponte—literally “Coconut Grove Bridge.” His nickname, Mossimkar, meant someone from Mozambique, much as Mumbaikar denotes a person from Mumbai.

Sequeira's Mozambique connection takes us back to the Prester John story behind Portuguese colonialism. The fifteenth century Portuguese kings convinced themselves that the mythical King ruled over the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia and eventually landed there with a diplomatic mission in 1520:

Source: adapted from mapswire.com

Although the Portuguese soon realized that Prester John had never ruled Ethiopia, this did not prevent them from acquiring colonial outposts in the continent. Modern-day Angola and Mozambique emerged as the principal territories of Lusophone Africa. When Antonio Joao de Sequeira traveled from Mozambique to Goa, he was moving within the Portuguese empire. The wealthy merchant later bequeathed the Fontainhas estate to Carmelite nuns.

When the pandemic-induced exodus from Old Goa, mentioned earlier, began, the arriving Portuguese purchased plots from the Carmelite nuns and built homes here. By the mid–nineteenth century, Fontainhas had become a residential neighborhood. The prevailing explanation is that the nuns sold off land in some haste, resulting in a quarter that grew with scant regard for planning principles. The planners of my city, Gurgaon, having enjoyed neither haste nor holiness, appear to have arrived at chaos by design.

Today, Fontainhas is zoned for mixed commercial and residential use. This creates understandable vexation for residents, as loud tourists gather outside their homes to take photographs. The colors are so Instagram-friendly that one feels nudged to frame the moment rather than live it. Daniel Kahneman distinguishes between two selves- the experiencing self and the remembering self. Much of experience now is mediated through the latter. I am hardly immune: I enjoy writing about what I have seen more than the act of seeing itself.

Many houses display signs prohibiting photography. As a result, I confined my camera to commercial establishments, with the exception of a few private homes that bore no warning signage. One such beautiful house is pictured below:

Walking through Fontainhas, I found myself standing before the Casa de Moeda—literally the House of Coins, or the Mint House—technically located in the adjacent Sao Tome ward:

According to an account by a descendant of one of the owners, the house’s original proprietor in the mid–eighteenth century was Joao Batista Goethalis, a businessman of Flemish origin from what is now northern Belgium, who married into a Portuguese aristocratic family. The building passed through several hands, one of which was the Royal Mint, which occupied it from 1834 to 1841. The Portuguese had established their first mint in Goa as early as 1521; the later move to this building formed part of the broader transition from Velha Goa to Nova Goa mentioned earlier.

Portuguese minting in India continued until the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1880, which rendered Portuguese coins obsolete and established the rupee–anna system as the sole legal tender. The treaty was the culmination of a relationship spanning more than three centuries, marked by Portuguese acquiescence to the supremacy of an ascendant Britain.

The arrival of the British East India Company in Surat in 1608 was accompanied by naval clashes, as Britain sought to break the Portuguese monopoly over Indian Ocean trade. Yet despite these skirmishes, the two countries were, historically, long-standing allies, their alliance dating back to the fourteenth century.

A pivotal moment in that alliance came in 1661, when Portugal ceded Bombay to the English crown as part of the dowry for the marriage of Catherine of Braganza to Charles II of England. The Portuguese had a pressing reason to seal a marriage with the British crown. As noted earlier, January 31, 1640—the date after which one of Fontainhas’s streets is named—marked Portugal’s declaration of independence from Spain and the rise of the House of Braganza, a powerful noble family, as the ruling dynasty. Spain, however, refused to recognize this transfer of power, making international legitimacy a pressing concern.

Charles II, perpetually short of funds, drove a hard bargain. The dowry included not just Bombay, but cash and Tangier, a strategic port on the Moroccan coast. The marriage also cemented a military alliance against Dutch imperial ambitions. As Jane Austen might have observed, it is a truth universally acknowledged that a king lacking a fortune must be in want of ready money—and perhaps a couple of strategic ports.

After Napoleon Bonaparte embarked on his expansionary wars in the early nineteenth century, Goa and other Portuguese territories in India came effectively under the shadow of Pax Britannica, not unlike the Indian princely states.

The Casa de Moeda stands in what is sometimes called Tobacco Square, named after the area’s anchor building—the General Post Office—which originally functioned as a depot for the tobacco trade:

The building opposite it is also owned by the Postal Department:

Around the dawn of the sixteenth century—when the Portuguese first set foot in India—they were also establishing colonial outposts in Brazil. One of the more profitable circuits they built linked Brazilian tobacco to markets in India and across Asia. Virtually unknown in India at the time, tobacco spread quickly, making its way into hookahs, khaini, zarda, and eventually into bidis wrapped in tendu leaves. Portuguese imperialism left behind not only churches and forts, but an addiction that proved far more durable than the empire itself.

The PIN code of the Post Office—403001—serves two destinations: Panjim and, improbably, Antarctica. In 1983, India established its first Antarctic research station. A year later, a post office was created to serve it—not on the ice, but via Goa. Mail addressed simply to “Antarctica,” with PIN code 403001, are routed to the National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research. From there, letters travel onward with scientists, supplies, and equipment to the Antarctic base. At the base, a research scientist acting as honorary postmaster cancels the stamps, formally marking the mail as dispatched. The cancellation prevents reuse—and stamps canceled in Antarctica are prized by philatelists.

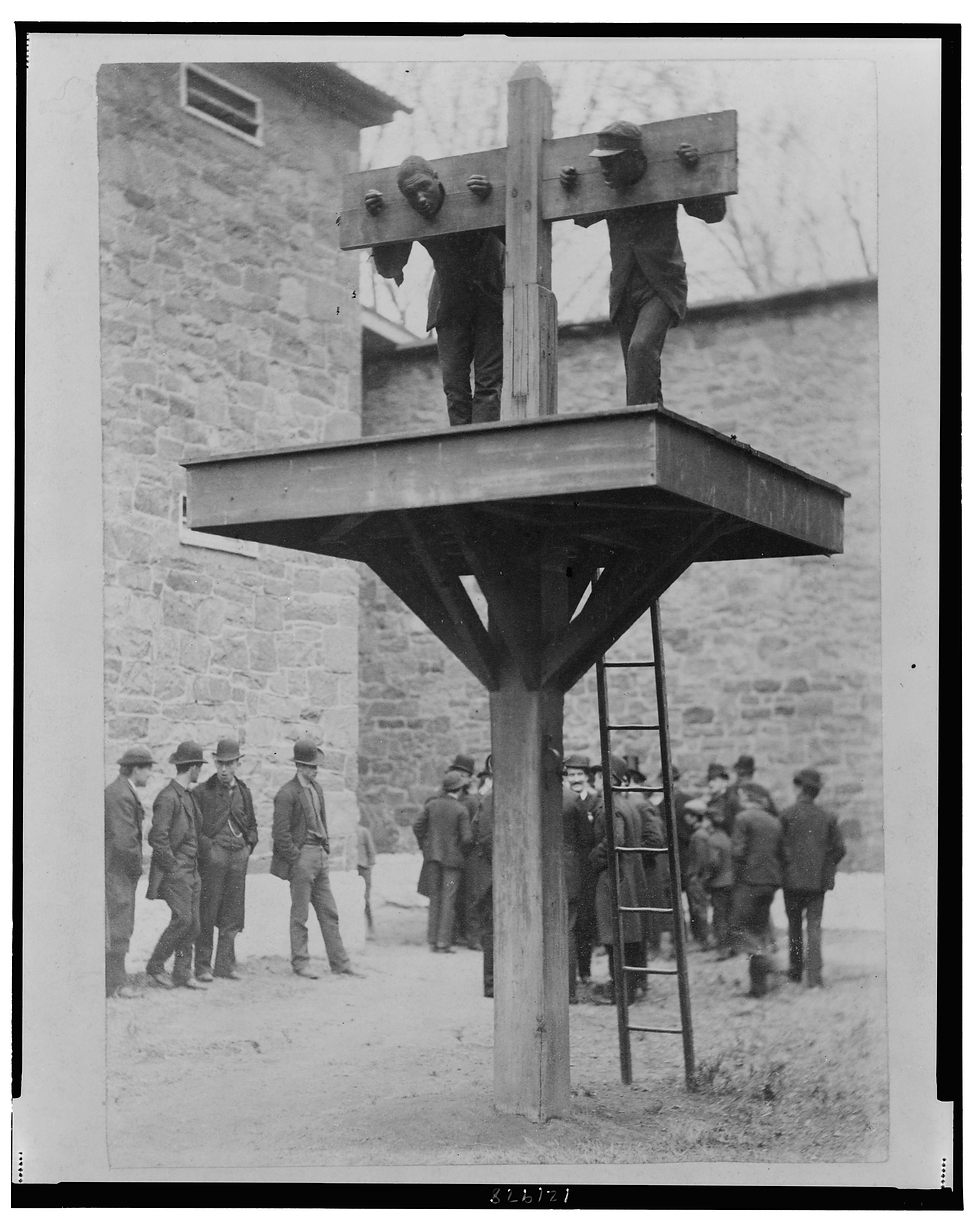

The Tobacco Square area outside the post office is known for something rather more grisly. It once hosted a pillory—a wooden frame with holes for the head and hands, used to restrain a person in public so they could be shamed. Below is an image from the American South showing two Black men being pilloried:

Source: Library of Congress

Compared to an afternoon spent pelting a stranger at a pillory, a few hours lost to Reels feels like moral progress.

At Tobacco Square, public shaming came with an upgrade option: executions were carried out at the same site. Presuming the clerks at the tobacco trading house in eighteenth-century Goa did not need to step outside for a smoke, they could still justify a breath of fresh air to witness a spot of public justice for entertainment. On December 13, 1788, fifteen men were executed here for plotting the Pinto Conspiracy. With that episode enters a critical strand of the Goan story—the long struggle for independence from Portuguese rule.

Goan society can be broadly divided by the timing of its colonial incorporation. The first group belonged to the Velhas Conquistas (Old Conquests), territories absorbed in the first half of the sixteenth century after the arrival of Vasco da Gama. The second were the Novas Conquistas (New Conquests), annexed in the latter half of the eighteenth century. The Old Conquests had previously been under Islamic rule, and many local Hindus, unhappy in that regime, reconciled themselves to Portuguese authority. In contrast, the New Conquests had lived under Hindu rulers and mounted sustained armed resistance to the Portuguese well into the twentieth century.

Within the Old Conquests, a segment of wealthy Brahmins was encouraged to improve its social standing through conversion to Christianity and marriage into Portuguese families. This strategy of cooption complemented the harsher alternatives of forced conversion through the Inquisition and the softer methods of Jesuit persuasion. Portuguese grooms benefited from substantial dowries, and this Catholic elite became highly Westernized. Many fled to Portugal around the time the Indian Army seized Goa on December 19, 1961.

The film Trikaal captures this world through the portrait of a wealthy Goan Catholic family. Its matriarch, Dona Maria Souza Soares, inadvertently summons the spirit of a Hindu nobleman betrayed by her grandfather to the Portuguese during a planchette session. Reality, of course, was more nuanced. Even among Catholic elites, opposition to Portuguese rule existed. The Pinto Conspiracy itself takes its name from three members of an elite Catholic family from the Old Conquests who played leading roles in the rebellion. Of the forty-seven conspirators arrested, many were native-born Goan Catholic clergy. Trikaal was filmed in the family home of Mario Miranda, who, despite his elite Catholic background, was cremated with Hindu last rites, as he wished.

Beyond the elite strata of the Old Conquests, both Hindus and Catholics participated in Goa’s freedom struggle, though their motivations were not always aligned with Indian nationalism. Hindu rulers in conquered territories may simply have been playing their own Game of Thrones. Some historians argue that the Goan priests who masterminded the Pinto Conspiracy were motivated less by ideology than by resentment at being denied advancement within the Church. Whatever their reasons, these early Hindu and Catholic rebels were unmistakably engaged in anti-colonial resistance.

Lest we imagine the Portuguese as grim figures occupied solely with trading spices, evangelizing, and executing rebels, they also made Indian food more interesting. They acted as conduits for crops from their New World colonies to India—tomatoes, potatoes, chili peppers, cashew, and pineapple among them. A food historian could trace how Goan cuisine emerged from this fusion of Portuguese and indigenous traditions. My task was simpler: to eat—and eat I did. After the Fontainhas leg of my trip, I had a traditional Goan thali at Postcard Saligao:

In the picture above, starting anticlockwise from the Goan red rice, are the green chicken cafreal and prawn curry, followed by urad methi dal—lentils and fenugreek seeds cooked in coconut paste. Goan food broadly falls into two traditions: Goan Catholic cuisine, with stalwarts such as vindaloo and cafreal, and Goan Hindu cuisine, where urad methi dal is a signature dish. There is also a variant of the daal that includes fish, prepared by pescatarian Hindus.

The pink concoction beside the dal is solkadi, typically consumed after a meal to aid digestion; its color comes from the skin of the kokum fruit. Completing the circle to the left of the rice is vegetable foogath, a simple stir-fry made with a chosen vegetable—cabbage, in this case. At the center sit fish fry and the local Goan bread, poee, of which I ate rather a lot.

One poee-based dish I ate at the hotel was a local variant of Maharashtrian thecha eggs—scrambled eggs cooked with cilantro, chilies, garlic, and peanuts, topped with potato crisps and served on poee:

Another variant was the Parsi Akuri—spiced scrambled eggs, again served over poee:

Another Portuguese legacy on the Indian dining table is beef. Outside the Northeast, it is widely available in the two Indian states where Portuguese evangelization left a large imprint: Goa and Kerala.

The Christian share of Goa’s population has declined from roughly a third at the time of its accession to India in 1961 to about a quarter in the most recent census. This shift reflects a combination of inward migration from elsewhere in India and the emigration of Goan Christians to Europe. During my visit, much of the service staff I encountered were non-Goans.

Under Portuguese law, those born in Goa before December 19, 1961—the date of Goa’s liberation—are eligible for Portuguese nationality, as are their children and grandchildren, even if born after annexation. A 2008 Goa migration study found that 75 percent of Goan emigrants are Christians, despite Christians comprising only about 25 percent of the population. This disparity is often attributed to greater Westernization, which may ease both employment prospects and assimilation in the West.

This emigration is often folded into a broader narrative about Goan Catholic nostalgia for Portuguese rule over Indian culture. The stereotype was reinforced in 2015 when it emerged that popular Goan singer Remo Fernandes had taken Portuguese citizenship in the 1990s, prompting questions about the propriety of his having received the Padma Shri and served as a brand ambassador for the Election Commission of India.

In 2018, Fernandes released a song whose lyrics include lines such as:

I love the Goa that I used to know, once upon a time a long time ago…

I love the Goa that I used to know… but she doesn’t exist anymore.

I do not think the song had anything to do with Fernandes’s Catholic background. During my trip, two cab drivers—one Muslim and one Hindu, both from families rooted in the region for generations—complained about the loutish behavior of “Indian” tourists. As someone who lives in Delhi, Occam’s razor suggests a simpler explanation: they were not stereotyping; they were reporting from the field.

Day 4

I began the day with a walk to the Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Church:

The church was built in 1609, more than two centuries before Saint Sebastian, when the administrative capital was still in Old Goa. In fact, a smaller chapel had stood on this site as early as 1541, when Panjim was little more than a fishing village. At the time, the river flowed close to the church; the surrounding land was reclaimed only in the mid-nineteenth century. Portuguese sailors entered Goa via the Mandovi, disembarked before the chapel, offered a thanksgiving prayer for the journey just completed, and then continued upriver to Old Goa, where the action was. The crisscrossing stairways above the red laterite steps were added in 1871.

Look closely at the steeple and you will notice a massive bell:

The bell was salvaged from a ruined church in Old Goa and brought here in 1874. It is sometimes called the “Inquisition Bell,” on the assumption that it announced the final trial of the condemned before the tribunal. One blogger argues that this reputation is misplaced: that grim distinction belongs instead to the bell at the Se Cathedral, one of the few major structures that still survives in Velha Goa.

Standing on the steps, one looks out over a broad square, beyond which begins the modern part of Panjim:

Looking farther out from this vantage point, the lush green Altinho hills come into view:

For breakfast, I stopped by the Confeitaria 31 De Janeiro:

The bakery has been around since 1930 and is a popular stop for photographers. It also gets very crowded. Not being a food aficionado, I refuse to wait in line, but when I arrived around 10:30 a.m. on a weekday, it was reasonably empty. By the time I left, a crowd had formed. I remain unsure what the fuss over the food is about—this is not a criticism of the bakery so much as a general skepticism. After all, how good can an omelette be!

The real purpose of the visit was to try the bebinca—the brownie-like confection in the picture below:

In seventeenth-century Portuguese Goa, convent nuns used egg whites to bleach their habits, leaving a surplus of yolks behind. A resourceful nun named Sister Bebiana—after whom the dessert is said to be named—turned this excess into invention, creating a sticky cake from egg yolks and the locally abundant coconut milk. Look closely at the photograph above and you will notice the horizontal lines slicing through the dessert. These are its layers. The original cake Sister Bebiana made had seven layers; the priest asked her to make it larger by adding more. The labor was Sister Bebiana’s; the priest’s role—mercifully less demanding—was to want more.

Even today, an acceptable bebinca—the kind that would not risk the baker’s excommunication—must have at least those original seven layers. Since each layer can take fifteen to twenty minutes to bake when done the traditional way, the process is labor-intensive. One hopes Confeitaria 31 De Janeiro was not practicing the same brand of “authenticity” I once witnessed at a Mexican restaurant in Arizona, where the chef conjured a menu item by emptying a bag of Doritos. Not that it may have mattered much: I found the bebinca perfectly harmless, without being anything I would seek out again.

The real issue, of course, is that taste is rarely just about flavor. It is bound up with a private archive of memory. For a Goan Catholic who ate bebinca at Christmas as a child—served by a grandmother, perhaps—it would taste unlike anything it ever could to someone like me, who lacks that personal and cultural context.

At this point, the broad historical arc should be clear. Portuguese navigation around the Cape of Good Hope led to Vasco da Gama landing at Calicut in 1498. Goa was acquired as a colony in 1510, with Velha Goa—about five miles from Panjim—serving as the initial administrative capital. From the mid-eighteenth century onward, epidemics drove the Portuguese out of Velha Goa and toward Panjim, which was christened Nova Goa and declared the capital in 1843. Fontainhas, the subject of this essay, emerged during this transition as a residential quarter for the arriving Portuguese.

Portuguese rule also produced a substantial indigenous Christian population through evangelization. In India, Portugal functioned largely as a subordinate power to Britain and faced anti-colonial resistance from various segments of Goan society from the late eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. In 1961, the Indian Army annexed Goa, bringing to an end a colonial regime that had lasted nearly four and a half centuries.

There was just one final act before I could tie a bow on my Fontainhas visit. I took a taxi to Old Goa—Velha Goa—the source of the people who shaped Fontainhas’s present form. Within half an hour, I was standing before the extraordinary Bom Jesus Basilica:

The basilica is one of only three major buildings that survive in Old Goa, a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site managed by the Archaeological Survey of India. Consecrated in 1605, it is one of the rare buildings where the side façade struck me as more compelling than the front:

As you draw closer, the side façade becomes even more imposing than it appears from a distance:

The name Bom Jesus translates to “Good Jesus” in Portuguese and is commonly used across Portugal and the Lusophone world. It is, for instance, also the name of a town in Brazil.

The Bom Jesus Basilica holds significance well beyond India within the Catholic world. It houses the body of Saint Francis Xavier, a central figure in the global history of Catholicism. Francis Xavier was a close associate of Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Society of Jesus—the Jesuits—in 1540. Unlike monastic orders that withdrew from society, the Jesuits worked directly in the world, becoming influential figures in education and founding schools and universities across continents.

The story begins on May 20, 1521, when the Spanish army was defeated by the French at the Battle of Pamplona. A Spanish nobleman named Inigo Lopez de Loyola, fighting as a soldier, was gravely wounded. In keeping with the customs of the time, French soldiers carried him back to his family estate in the Basque country. He spent his convalescence comparing his emotional responses to different daydreams, noting that fantasies of knightly romance left him empty while thoughts of saintliness brought spiritual fulfillment. This insight led him to abandon his military ambitions and devote his life to God. More than a century later, Ignatius of Loyola would be canonized as a saint.

Photograph of painting in a church in Michigan depicting Ignatius renouncing the world

Source: Library of Congress

Francis Xavier, like Ignatius, was born into a noble family. In 1529, at the age of twenty-three and while studying in Paris, he befriended the fifteen-years-older Ignatius. Initially skeptical of Ignatius’s call to spiritual renunciation, Francis was eventually persuaded. In 1534, he joined Ignatius and five others in taking vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to the Pope.

The trope of young men of educational or economic privilege renouncing worldly life recurs in both religious and secular history. In 1885, the Cambridge Seven—elite graduates of Cambridge—abandoned promising careers to become missionaries in China. In the 1870s, the Narodniks were young Russian intellectuals who gave up privileged lives to “go to the people,” hoping to radicalize the peasantry through education and agitation. In the late 1960s, the Naxalbari movement drew thousands of highly educated young men away from lucrative careers to fight feudal repression in India. What distinguishes the act of the seven Jesuit men on the hill of Montmartre overlooking Paris is not renunciation itself, but the institutional durability they created from what elsewhere often remained a brief flare of youthful ardor.

In 1540, the King of Portugal, through his ambassador to the Vatican, requested missionaries for his Asian colonies. Ignatius responded by dispatching Francis Xavier. While novels and films dwell on the glamorous upper reaches of the Raj, the colonies were also populated by soldiers, sailors, tradesmen, and even ex-convicts—working-class men who could live as “gentlemen” overseas. When Francis arrived in Goa in 1542, he began by ministering to these humbler Portuguese expatriates before turning his attention to the indigenous populations along India’s southern coast. From India, he traveled widely across Asia, including to Japan and China. In December 1552, during one such mission, he died on an island off the southern coast of mainland China. The story of his body as commonly narrated by believers is as follows:

St. Francis Xavier was buried at the island by his Chinese friend Antonio de Santa Fe in a wooden coffin, following local custom. At the suggestion of one of the four attendees of the burial, the coffin was packed with quicklime to hasten decomposition of the body inside and make the later transfer of bones easier. A couple of months later, when a ship was about to sail to Malacca—a Portuguese colonial outpost in Malaysia, the grave was reopened to retrieve and ship the remains. The body was found intact, showing no signs of decomposition and was shipped to Malacca in the coffin.

In Malacca, he was buried again by the local faithful, this time without a casket. Since the burial pit was short for his frame, his head was pressed down over his chest, thus breaking his neck. There the body remained for five months. Then Juan de Beira—the successor priest of Francis in the Malacca parishes— with the help of a friend, had the grave secretly opened so that he could view his idol's remains. When they found that the body had still not decomposed, they secretly shipped the body 4000 kilometers to Goa, where it still lies in a casket within the Bom Jesus Basilica.

The casket is moved to the nearby Se Cathedral once every ten years for public viewing. Below is an image from the most recent decennial exposition in 2024, reproduced from a coffee-table book I picked up at the souvenir store:

The tradition of public display arose from rumors circulating in the late eighteenth century that the saint’s body had been replaced by another. Although the casket can be seen daily at the Bom Jesus Basilica, the body inside is not clearly visible there. The decennial exposition serves, in part, as reassurance.

There is further macabre detail for those inclined to such things. Over time, the body of Saint Francis Xavier has been subjected to what might be called respectful mutilation, driven by the demand for relics among Catholic institutions in India and abroad. According to one account, the first occurred aboard the ship carrying the body from the Chinese island to Malacca. Struck by its extraordinary preservation, a sailor cut away a small piece of flesh—roughly the size of a finger—from below the left knee to serve as proof.

The term incorrupt is overstated, but it is true that the body is far less decomposed than one would expect, given that no known embalming technique was used. In some Christian traditions, incorruptibility is seen as a miraculous sign of exceptional holiness; such bodies are even said to emit a pleasant aroma. The Catholic Church, however, does not treat incorruptibility as a condition for canonization.

In The Brothers Karamazov, when the monk Zosima’s body begins to smell within hours of his death, onlookers whisper that this proves he was insufficiently holy—surely God would not allow such indignity to befall the truly pious. Alyosha, the protagonist, whose faith in and love for his mentor remain unshaken, is wounded by what feels like divine unfairness. Dostoevsky uses this episode to argue that faith does not rest on spectacle, miracles, or ritual. Divinity, he suggests, lies instead in active love: engaging with others in the mundane rituals of life, accepting their imperfections, sharing their sorrows, and treating them with kindness.

The Jesuits embodied this outward-facing engagement with the world. In India, many of the best schools and colleges are Jesuit-run. I was myself fortunate to study for three years at a Jesuit school in Patna, and I was born at the Holy Family Hospital there.

Reconciling Jesuit piety with the Goa Inquisition, however, is difficult. How could seven men swear obedience to a Pope who presided over a parallel machinery of torture? There is no satisfying answer, except that it speaks to the duality of human nature. To paraphrase Dickens, we are at once the best of people and the worst of people.

From the entrance door, the beauty of the Bom Jesus Basilica reveals itself slowly, drawing the eye inward toward a quiet, accumulating grandeur:

Photography is not permitted inside the basilica, which is why the inscription on the altar table is not visible in the photograph above. Up close, however, it is unmistakable. It reads “Hi Mhoji Kudd”—a Konkani phrase meaning “this is my body.” While the language is Konkani, the script is Roman, the same Latin alphabet used for English. Romi Konknni, or Konkani written in the Roman script, is one of the five scripts in which Konkani can be rendered and is widely used in Goan Catholic literature.

Like many Indian languages, Konkani is tightly bound to cultural—and therefore political—identity. After India annexed Goa in 1961, the question arose of which state Goa should belong to. A decade earlier, Potti Sriramulu’s fast unto death for a Telugu-speaking state had jolted post-independence India into accepting linguistic reorganization. Yet statehood for Goa on the basis of Konkani was a non-starter, since it would have required carving Konkani-speaking regions out of neighboring Maharashtra and Karnataka. Curiously, Portuguese—which became dominant in Brazil—never took firm root in Goa, perhaps a consequence of the linguistic gravity exerted by British India.

Many Goans—especially Konkani speakers—wanted Goa to be a separate state within India. Others, fluent in Marathi, favored merger with Maharashtra and argued that Konkani was merely a dialect of Marathi. The dispute carried a religious inflection. While almost everyone in Goa spoke Konkani, a majority of Hindus also spoke Marathi; the Konkani–Marathi divide thus intersected with Catholic–Hindu identity. As noted earlier, a segment of elite Catholics, culturally aligned with Portugal and wary of discrimination by a Hindu majority, even favored independence as a separate country.

Confronted with these competing claims, the Indian government did what it often does in such situations—nothing. A prime minister once observed that not taking a decision is itself a decision. Goa was therefore left in a suspended state, administered directly by the Union, not unlike Washington, D.C..

Naipaul famously called India a land of a million mutinies. In Goa alone, several were on display: Hindus versus Christians; Goans versus Maharashtrians; Konkani speakers versus Marathi-leaning Goans; Portuguese-identified elites versus Indianized Goans. Even this list omits the caste fractures within Goan Hindu society. Some in India argue for single-party rule on the Chinese model. Yet the diversity sketched here—within a population of just 1.5 million, smaller than Chicago—suggests that suppressing Naipaul’s million mutinies would risk balkanization. Parliament, messy as it is, remains India’s greatest achievement.

India does not favor Brexit-style referendums or direct ballot initiatives of the kind common in the United States. There have been just two exceptions. One was the 1967 Goa referendum, in which Christians and sections of the Hindu population formed a tactical alliance to defeat merger with Maharashtra by a margin of 54–46. Goa remained a centrally administered territory until 1987, when it was granted full statehood. That same year, a parallel law adopted Konkani as the official language of Goa. In 1992, Konkani was added to the Constitution of India as one of the country’s twenty-two official languages. It is often said that a language is a dialect backed by an army. By that measure, Konkani had finally arrived.

All this history loops back to “Hi Mhoji Kudd”—the Romi Konknni inscription inside the Bom Jesus Basilica. One might expect that at least the pro-Konkani faction of Goans would have been satisfied when Konkani became the state’s official language in 1987. But that would be too tidy an ending since this is India. The legislation recognized Konkani written in the Devanagari script, while many Catholics preferred the Roman script. Romi Konknni, it turned out, had won the language but lost the alphabet.

Romi Konknni is not merely a script but also a dialect within Konkani, with certain words carrying subtly different meanings from their Devanagari counterparts. Its popularity among Catholics stems from liturgical practice: much of the Church’s worship uses it. The reason, in turn, is prosaic. Portuguese missionaries in the sixteenth century found it easier to publish their texts in the Roman script because the printing presses they brought to India were equipped with Latin type. Romi Konknni, then, was born less of theology than of typography—a technological workaround that hardened into tradition.

It may surprise the world, though not Indians, that decades of political debate ended by pleasing no one. Konkani-supporting Catholics did not get the script they wanted, while Hindu supporters of Marathi did not get the language they preferred. Democracy, in the end, asserted itself not by choosing sides, but by disappointing everyone with scrupulous impartiality.

That “writing technology” can shape how we communicate is less strange than it first appears. History offers many examples. The advent of the printing press led to the standardization of English grammar and spelling. At first, printers merely reproduced what authors submitted; soon enough, they began imposing their own norms. This influence extended beyond spelling to matters of dialect. By one account, printers favored the Northern English plural pronouns they, their, them over the Southern hi, hir, hem. More recently, the character limits of early SMS culture produced acronyms like LOL, OMG, and FYI. Virtual keyboards, in turn, have given rise to emojis—forms that hover somewhere between written and spoken language.

On the opposite side of the Bom Jesus Basilica stands the Se Cathedral of Santa Catarina:

Not visible in the photograph above—owing to its height—is a golden bell housed in the chamber of the left tower. It is the heaviest church bell in Goa and, as noted earlier, may have been the one tolled during Inquisition proceedings. The right tower collapsed in 1776 and was never rebuilt. Erected to commemorate the 1510 Portuguese conquest of Goa, which occurred on the feast day of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, the Se Cathedral of Santa Catarina was begun in 1562, completed in 1619, and consecrated in 1640. The nearly eight decades of construction reflect an interruption in funding during the period when Portugal was under Spanish rule.

Photography is permitted inside, provided no other person appears in the frame. This is easier than one might expect because, despite being just across the road, the cathedral draws far fewer visitors than the neighboring basilica. I took a few photographs of the interior:

Sitting in the cathedral, I found myself imagining those who had occupied this space centuries ago—perhaps a Portuguese mother praying fervently for her child’s survival at a time when epidemics were common and germ theory unknown. Human life then, and for much of history, was, as Thomas Hobbes put it, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” It is easy to be swept up by architectural splendor, yet the essential human dramas remain unchanged—whether played out in gilded courts or crowded tenements.

Across the basilica, the precinct that houses the cathedral also contains the Archaeological Museum of Goa:

In the photograph above, the Se Cathedral of Santa Catarina stands on the right, the Church of St. Francis of Assisi occupies the center, and on the far left is the museum housed in the former convent attached to the church. Old Goa thus contains a basilica, a cathedral, and a church. For the uninitiated, these terms carry specific meanings within Catholicism. A basilica is a church granted special status; the Vatican designated the Bom Jesus Basilica as one in 1946. A cathedral is the principal church of a diocese and the seat of a bishop. All basilicas and cathedrals are churches, though a church may be neither—or, in some cases, both.

After returning to Fontainhas from Old Goa, I walked to Cafe Tato, just outside the Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Church, and had poori bhaji for lunch:

Despite—or perhaps because of—its oiliness, the food was quite delicious. Cafe Tato is cheap, quick, and unpretentious, but its chief claim to fame is that Sachin Tendulkar is said to be fond of the food:

Finis

The original residents of Fontainhas, though often affluent, were largely what gamers would call non-playing characters—figures who populate the world, enable interaction, and advance historical forces over which they exercise little control. They lived through European colonialism, Christian evangelization, the Inquisition, local wars, shifting power dynamics in Europe, pandemics, anti-colonial uprisings, and finally the Indian Army’s annexation. Some—like the mossimkar—made long journeys from Lisbon to Goa via Mozambique; others were born and died within Goa itself. Their lives were shaped by history, but not consumed by it. Amid upheaval, they lived ordinary lives marked by courtship, marriage, parenthood, loss, and grief. As visitors from another time and place, our understanding can only be intellectual; we cannot know how it felt to live through those moments. All we can do, walking these lanes today, is acknowledge that history happened here.

For the reader patient enough to reach this far: God bless you—or, as they say in Konkani, Dev Borem Korum.

Comments